Honest John

Rocket Artillery (Nuclear)

The sign in front of this Honest John, at the US Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, is like many such signs throughout the country in that it provides no hint that the weapon is a nuclear weapon.

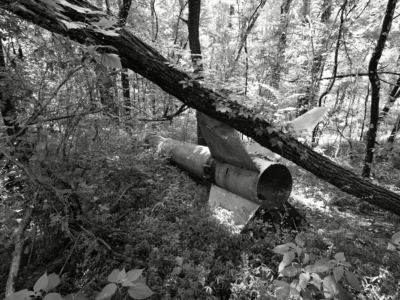

Honest Johns could be fitted with non-nuclear warheads. After the early 1970s the Honest John was primarily a non-nuclear weapon fielded by state-based units, such as this one Camp Mabry in Austin, Texas, headquarters to the Texas Military Forces.

When assigned to duty in military units the Honest John was painted olive drab but weapons used for testing were painted in a variety of colors and patterns to help observers track the weapon in flight and to better determine its rate of spin. Located at the Nuclear Museum in Albuquerque.

A second Honest John at the Nuclear Museum in Albuquerque. Many sources claim the the weapon could be deployed and launched in five minutes. That seems simply impossible, as a video of the process–a video heavily edited to compress the time–is five minutes long.

The Honest John is an uncommonly popular weapon display, often at non-military locations. This Honest John, at a middle school, has been there so long none of the school staff, save a guard I met with a special interest in atomic weapons, seems to know that it is a nuclear rocket. Located in Neenah, Wisconsin.

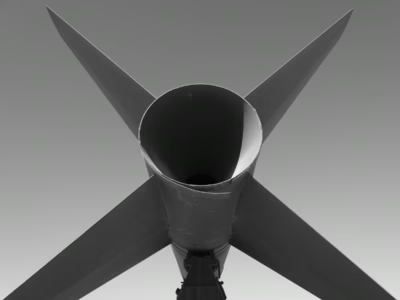

The warhead of the Honest John would often be a nuclear explosive but it could also be a more traditional high explosive (surrounded by tens of thousand of small ball bearings for maximum destructive effect to enemy personnel, a sarin gas warhead, or a cluster munition with 4800 M40 grenades.

Most of the Honest John launches seem in historic videos took place at the White Sands Missile Range, in New Mexico. They have an extensive rocket garden just inside the fortified gate to the base.

The Honest John could be assembled and then driven to its destination, though it seems it was usually assembled at the launch site. The example is at the Yuma Proving Ground, in Arizona.

The middle section of the Honest John held the propellant, which apparently operated best at 77 degrees Fahrenheit. To help achieve this a warming blanket was placed over the rocket when being transported. It is entirely unclear how the rocket would be cooled if the Sun warmed it above 77 degrees, or what the actual thermal operating range of the rocket might be if it could not be held at the proper temperature. This unit baking in the heat at the Yuma Proving Ground, Arizona.

The Honest John was an unguided missile and would be launched off its truck-mounted platform with a dramatic burst of flame. The propellant would, however, last only a few seconds before sending the rocket on its way. Yuma Proving Ground, in Arizona.

An Honest John at the Yuma Proving Ground. Its paint job, which indicates it was intended to be a test model, looks surprisingly modern as many contemporary nuclear weapons are painted white.

An Honest John displays at Camp Atterbury, a National Guard installation in Indiana. The historic weapons area is located just past the main gates and open to the public. Note that the lower two fins on the rocket have ben removed (very common to see) presumably to avoid people banging their heads on the fin’s edge.

Here you can see the Honest John mounted in its launch vehicle, which has its three ground stabilizers deployed to attempt to keep the rail stationary as the rocket launches. In the historic films of test launch the rail seems to move quite dramatically, although the Army claims that the rocket, especially the newer versions, has good accuracy. Yuma Proving Ground, Arizona.

The Honest John, with a maximum range of fifteen miles in its first version and thirty miles in its improved version, was seen as a weapon to support ground troops, destroying enemy formations and bridges in and just behind enemy lines. Located at Camp Atterbury, part of the Indiana National Guard, near Edinburgh, Indiana.

An Honest John posed outside of an Army-Navy Surplus store in Bedford, Indiana. Given the number of Honest John’s on display in the United States I’m assuming that at some point a large number of them (rendered inert, of course) were sold as surplus.

Not many homes come with a view of a nuclear weapon. These homes in Crestwood, Illinois are among the lucky few. The Honest John is positioned at the corner of a sizable municipal park.

Cultural differences surely play a great role in the display of nuclear weapons in public space. This Crestwood, Illinois installation would never be permitted along the northern California Coast, where I live. On the other hand I know of no neighbors who have served in the Armed Forces or have children in the Armed Forces.

This Honest John, painted with the word “Missiles,” is the school’s mascot and football team namesake. It has long guarded the building now used by the Milledgeville Middle School, in Milledgeville Indiana.

The guard at this school, the Milledgeville Middle School in Milledgeville, Indiana, was surprised to learn that the rocket out in front of the school was a nuclear weapon.

Over seven thousand Honest Johns were made and were deployed not only US bases but to allied bases worldwide. It is easily one of the most successful nuclear weapons ever made, owing no doubt in large part to its comparatively low cost, its ease of use, its size (which code be transported by air), and its high mobility. Located in Milledgeville, Indiana.

The bartender at the American legion Post 1019 in Kankakee, Illinois alerted me that he had heard that the fins on this unit, located in the parking lot to the post, were not the original ones and that the originals were larger.

This roadside Honest John is located in St Albans, along the extraordinarily busy MacCorkle Avenue, is technically inside the small Rosie the Riveter Park but it’s far better to navigate to it by looking for the McDonalds, just across the street. Parking is available in a playground and picnic area just past the rocket, on the riverside, heading west.

A cutaway view of an Honest John warhead at the Artillery Museum deep inside Fort Sill, Oklahoma. This display show the warhead holding 4800 grenades which would disperse before impact, to be used against massed enemy troops.

Explosive Power

15 kt. (early) or 2-30 kt.

Hiroshima Equivalent Factor

Up to 2x

Dimensions

27 ft. 3 inches x 30 inches (early version)

Weight

5820 lbs (early version)

Year(s)

1953-1991

Range

15 (early) or 30 miles

Purpose

First nuclear rocket artillery

Nukemap

NUKEMAP is a web-based mapping program that attempts to give the user a sense of the destructive power of nuclear weapons. It was created by Alex Wellerstein, a historian specializing in nuclear weapons (see his book on nuclear secrecy and his blog on nuclear weapons). The screenshot below shows the NUKEMAP output for this particular weapon. Click on the map to customize settings.

Videos

Click on the Play button and then the Full screen brackets on the lower right to view each video. Click on the Exit full screen cross at lower right (the “X” on a mobile device) to return.

Further Reading

- Wikipedia, Designation Systems.

- The first version of the Honest John used a variant of the Mark 7 bomb as a warhead. Later versions used the W31 warhead, which was also used in the Nike-Hercules and the ADM (Atomic Demolition Munition). [Link to American Nukes forthcoming.]

- I haven’t seen it mentioned in any history yet but read the “Memorandum From the Joint Chiefs of Staff to Secretary of Defense McNamara” which, in 1961, recommended a demonstration launch with a live nuclear warhead (and subsequent real nuclear detonation) of an Honest John (and an Atlas and a Polaris–Army, Air Force, Navy, you see, all live demonstrations) in order to cow the Soviets–the Berlin Wall had gone up two months before this memo.

- The Honest John could be armed with a nuclear warhead but also a sarin gas or high explosive warhead–some countries only had the non-nuclear versions. How were the Soviets to tell the difference? “Paint The B-52s Brightly: Reducing Confusion Between Conventional and Nuclear Weapons is Essential” by Christine Parthemore and Catherine Dill lays out the issues in War On the Rocks.

- The US Army’s timeline of the life of the Honest John rocket.

- Rénald Fortier, writing in his signature style at the Ingenium Channel, shares his blog post “…A brief yet frightening look at the Douglas M31 and M50 / MGR-1 Honest John…” and Part 2. Lots of good stuff there (including an alternative theory on the origin of the name “Honest John”), keep reading.

- An excellent overview of “Honest Johns in Korea” written by Jeffery Lewis at Arms Control Wonk. Don’t miss the bathroom story.

- The US Marines wanted Honest Johns, just like everyone else, as recounted by Jonathan Bernstein in his “Atomic Leathernecks: Nuclear Rocket Artillery in the Cold War,” published by the Marine Corps Association.

- Canadian forces stationed in Europe fielded Honest Johns: “Artillery in Canada: 762-mm M50 Honest John Rocket” by Harold A. Skaarup at his blog, SilverHawkAuthor.

- A short, informal history of the 2nd Missile Battalion, 42nd Artillery, an Honest John unit. Be sure to see the unit group photo.

- An interesting image of an Honest John on its launch platform, from Stars and Stripes. Note the warming blanket over the rocket motor area–the propellent worked best at 77 degrees.

- How do museums get their Honest Johns? This is how the Nuclear Museum got one of theirs.

- Want a user manual to the Honest John? Try this 1972 field manual (not a typo, they were still around until the 1980s), “Field Artillery: Honest John Rocket Gunnery” from Headquarters, US Department of the Army (rubber stamped “Room 1 A 518 Pentagon).” Pay special attention to Chapter Four and its instructions on using the FADAC, the first field artillery semiconductor-based computer.