Little Boy

Science and industry Build a Weapon

A Little Boy replica at the Bradbury Museum of the Los Alamos National Lab. The is in the main exhibit gallery but is not the star of the show by any measure, perhaps understandable given Los Alamos many other activities over the years and their desire to highlight their work that benefits non-military purposes.

At Wings Over the Rockies, an aerospace museum in Dallas. This Little Boy sits on its transport cart (uncommon to see). You can see the bomb again with its cart is image #4 of the model plane being loaded.

The same display as image #2. The plane that the bomb appears to “go with” has no relationship to it at all. It is a B-18 Bolo and the weight of Little Boy was more than twice the plane’s entire bomb load capacity.

In this model from Wendover Historic Airfield (where Tibbets and crews trained to drop the Little Boy and Fat Man bombs) you can see the bomb loaded via special loading pit. The B-29 would drive up over the bomb which would be lifted up into the plane. Even for these B-29s the weight of the bomb was so great that the plane would jerk sharply upwards upon release of the weapon.

One of the most famous individual planes in history, this is the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima, on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, the annex of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, located just outside of Washington, DC, in Chantilly, Virginia. A bomb is nothing without a plane to deliver it and few planes in the world could carry the weight of Little Boy. The Boeing B-29 Superfortress (its development the most expensive of all the weapons programs in WWII, easily surpassing the cost of the entire Manhattan Project) is a central part of the story of Little Boy and Fat Man, though often underemphasized.

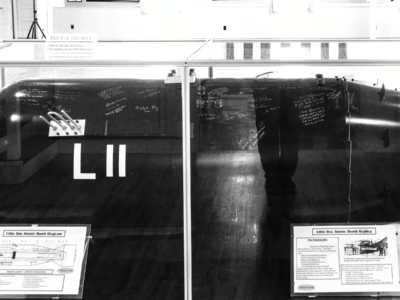

A model of Little Boy located at Wendover Historic Airfield, in Utah, on the California border. The base, once neglected, is now being restored. This model, made by John Coster-Mullen, is considered one of the most accurate and is a centerpiece of the historical base, though the weapon was never here. Wendover was where the crews of the B-29s practiced dropping the bomb.

A close-up of the same bomb, where you can see the the signatures of Paul Tibbets and other crew members of the Hiroshima mission (the crew visited in 2004). You can see Tibbets’ signature center right, written large–the same location Tibbets signed the original Little Boy. In addition, according to John Coster-Mullen, who made the replica along with his son, Jason, the three remaining crew members of the Enola Gay also signed (he does not name them) as well as the widows of Ferebee, Beser, Downey, and the nephew of Fred Olivi, along with others. The replica was signed at the 509th reunion in Wichita, Kansas in 2004.

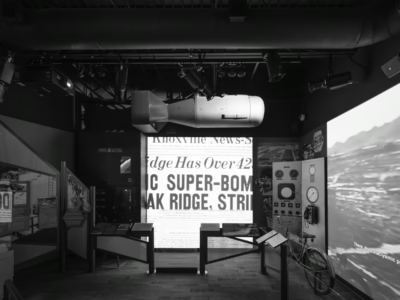

An image from the new galleries at the K-25 History Center at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, the site where uranium was purified for use in Little Man and for further processing into plutonium in Washington state. The display emphasizes the many other locations (in addition to the famous Los Alamos) that worked on developing the bomb.

Explosive Power

15 kt

Hiroshima Equivalent Factor

1x

Dimensions

10 feet x 28 inches

Weight

9700 lbs

Year(s)

1945

Purpose

Force Japanese surrender

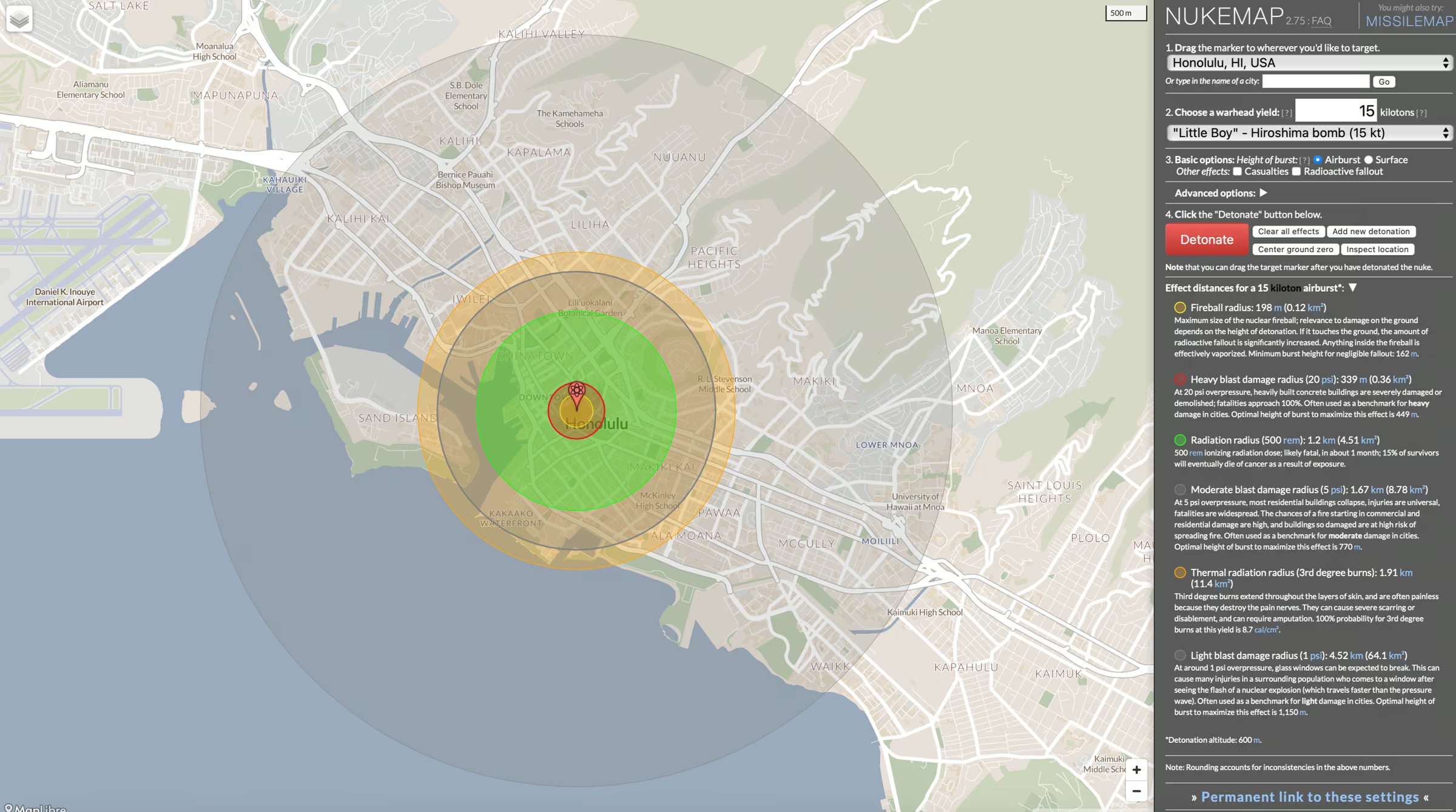

Nukemap

NUKEMAP is a web-based mapping program that attempts to give the user a sense of the destructive power of nuclear weapons. It was created by Alex Wellerstein, a historian specializing in nuclear weapons (see his book on nuclear secrecy and his blog on nuclear weapons). The screenshot below shows the NUKEMAP output for this particular weapon. Click on the map to customize settings.

Videos

Click on the Play button and then the Full screen button on the lower right (the brackets on a mobile device) to view each video. Click on the Exit full screen button (the “X” on a mobile device) to return.

Further Reading

- Wikipedia, Atomic Archive, and the National WWII Museum (New Orleans).

- If there is a standard text on the first nuclear bombs it is undoubtedly The Making of the Atomic Bomb, by Richard Rhodes, for which he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1987. I read it cover-to-cover when it came out in paperback in 1988 when I was in my early 20s.

- Although Oppenheimer is the star of the bomb development show in the popular imagination (as is generally though inaccurately credited with leading the Manhattan Project) the actual director of the Manhattan Project was Leslie Groves, who later wrote an account of his experiences, Now It Can Be Told: The Story Of The Manhattan Project. Oppenheimer worked for Groves on the design of the weapons, Kenneth Nichols had the responsibility for producing the nuclear material for the bombs. He wrote a book, too: The Road to Trinity. Both are fascinating day-by-day accounts of the development of the first nuclear weapons written by participants (indeed, by some of the leadership) of the development of the bombs.

- Coming out first as a single-article New Yorker issue and then a book, both published just weeks after the bombing of Hiroshima, no other publication has more greatly shaped public attitudes toward the bomb as those attitudes were first forming than John Hersey’s Hiroshima. Covering a half dozen graphic, sometimes horrific, first-hand accounts from survivors of Little Boy, this slim book has been in print continuously from October 1946 to today. (Finally available in Russia starting in 2020).

- War today seems distant and increasingly abstract to most US citizens. While neither Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-1945 by Max Hastings nor Hitler: Downfall: 1939-1945 by Volker Ullrich are “nuclear weapons” books, both will give a clear sense to the reader of the total war for national survival that was World War II and that had Japan, Germany or Russia had an atomic bomb they would, of course, have used it.

- Yoshito Matsushige was a photographer for the local paper, Chugoku Shimbun, in Hiroshima when Little Boy was dropped. Over a hundred of his co-workers were killed and the newspaper’s building was destroyed, but Matsushige survived and made several images of the aftermath of the bombing. The paper still publishes and maintains a we page honoring his work-be sure to click on th expandable action at the bottom.

- The National Archives has an extensive online collection of primary source material on the Hiroshima (and Nagasaki) bombing worth exploring. See also the collection at the National Museum of the US Navy.

- John Coster-Mullen was an industrial photographer (and truck driver) who was also a well-known amateur nuclear archeologist, notably discovering in the late 1990s that all of the previously published diagrams of the internals of Little Boy were inaccurate. He is the subject of a short, slightly condescending NPR profile, “North Korea designed a nuke. So did this truck driver,” and a much fuller New Yorker profile, “Atomic John.” He published his own book, Atom Bombs: The Top Secret Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man (this Amazon listing is apparently from his estate) and Alex Wellerstein (of NUKEMAP fame) wrote a touching obituary.

- Coster-Mullen,along with his son Jason, built a full-sized replica of Little Boy in 2004, commissioned by the Historic Wendell Airfield, in Utah. While driving the replica across country he stopped at Wichita for the reunion of the 509th Composite Group (the unit responsible for dropping the atomic bombs on Japan) and his Little Boy was signed by Paul Tibbets, the pilot of the Enola Gay, and others from the crew and their families. Here is a behind the scenes [download] look at the model as it was being built, with photos.

- M.G. Sheftall’s Hiroshima: Last Witnesses is an eye-opening book telling the story, based on numerous interviews of those who survived Little Boy, of efforts to rescue and treat victims, efforts to dispose of the tens of thousands of bodies, and the lingering effects–physical, emotional, and political of the atomic attack.