Mark 36 Bomb

A bomb for every city

The Rockwell B-1A Lancer (one of four of the “A” model that were built in the 1970s) was a bomber built to carry nuclear weapons. However, the Mark 36–poised to be loaded into it as you can see here–was retired ten years before this plane was built. At the Wings over the Rockies Museum in Dallas, Texas.

The casing of the Mark 36 was made of aluminum in an effort to save weight. The casing, however, was 3.5-inches thick and the casing alone weighed 12,000 lbs. This example is located at the SAC Museum, in Ashland, Nebraska.

The nuclear test Operation REDWING CHEROKEE, in 1956, was there first time a thermonuclear bomb had been dropped. Some writers say it was a Mark-17, some say it was a TX-15. Author Peter Goetz thinks it was a Mark 36, basing his logic on comparisons to the Mark 17–he doesn’t mention the TX-15. In any event, the plane dropped the bomb four miles off course and little scientific data was gained. This bomb is at the SAC Museum in Ashland, Nebraska.

Explosive Power

6 or 19 Megatons

Hiroshima Equivalent Factor

400x or 1267x

Dimensions

12.5 feet x 4 ft. 11 inches

Weight

Approx. 17,700 lbs.

Year(s)

1956-1962

Purpose

The primary nuclear bomb in the late 1950s

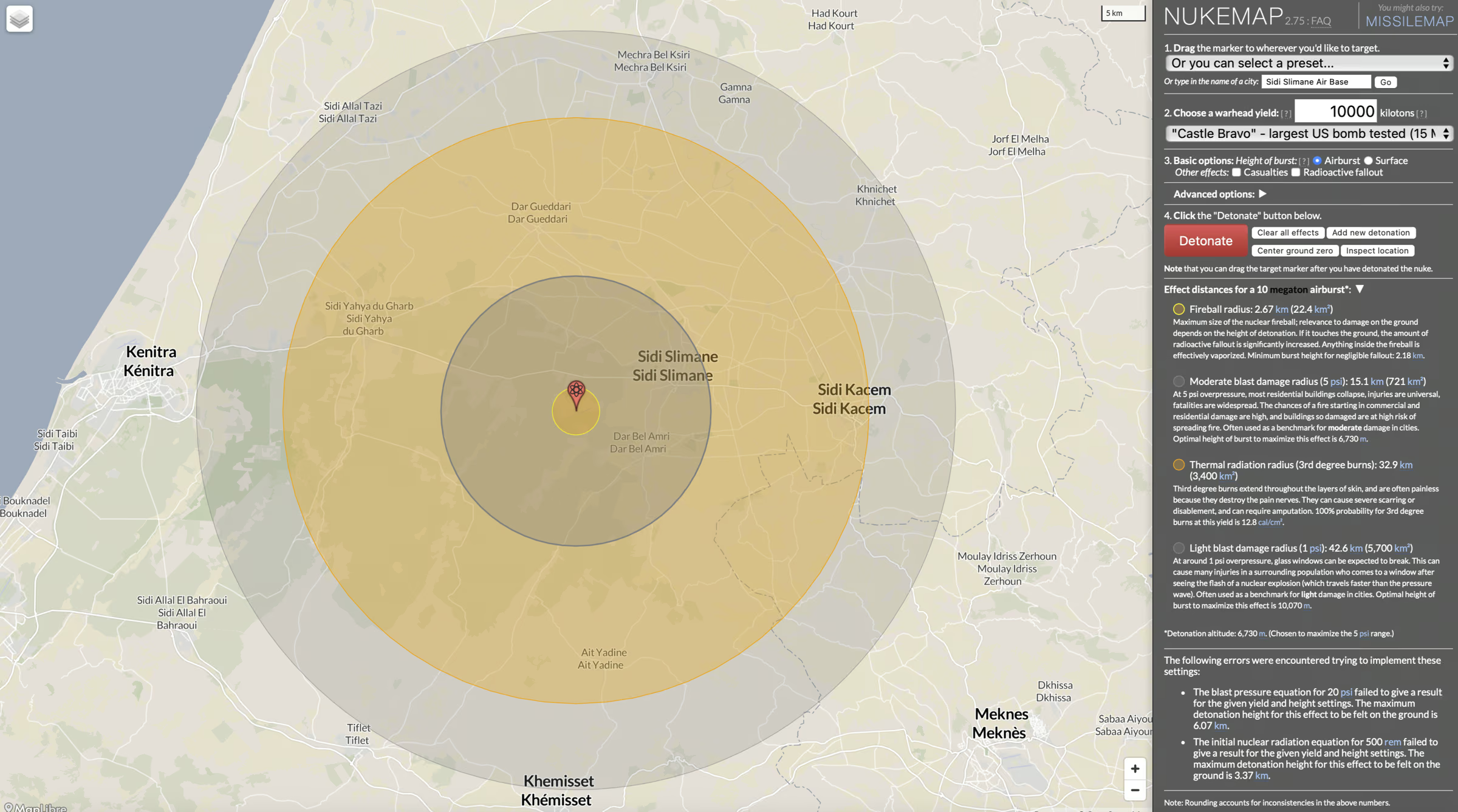

Nukemap

NUKEMAP is a web-based mapping program that attempts to give the user a sense of the destructive power of nuclear weapons. It was created by Alex Wellerstein, a historian specializing in nuclear weapons (see his book on nuclear secrecy and his blog on nuclear weapons). The screenshot below shows the NUKEMAP output for this particular weapon. Click on the map to customize settings.

Videos

Click on the Play button and then the Full screen brackets on the lower right to view each video. Click on the Exit full screen cross at lower right (the “X” on a mobile device) to return.

Further Reading

- Wikipedia

- I have not yet found any videos worth posting on the Mark 36 but the video I did post, Power of Decision, is a near perfect illustration of the pre-ICBM thinking in the Air Force during the time the Mark 36 was in service. Made by the Strategic Air Command and “published” (it was classified) in 1958, the film depicts a nuclear war from the perspective of Air Force commanders. It has strong pre-echos of Dr. Stangelove and the film is unintentionally (and very darkly) funny by the end as they calmly reveal that the US has suffered 60 million casualties–of those, 40 million dead–in the four day, victorious war. Oddly, the bombs, briefly shown as they drop, appear to be Mark V models (not thermonuclear bombs, though the explosions certainly are). Likewise, the Rascal and Bull Goose are shown being launched, despite both never entering service, among other anomalies.

- There have been many nuclear accidents. In one especially significant incident, a US bomber in Morocco carrying a Mark 36 with the nuclear core set up for insertion, caught fire on the runway and burned, melting the bomb. There are many versions of the story–the best is probably by Eric Schlosser, whose book Command and Control is one of the most informative books on nuclear weapons that I have encountered, and from which this excerpt is taken. Louis Menand’s review of Command and Control in The New Yorker magazine which touches the Moroccan accident, and other issues as well, is worth your time.

- A beautifully done chart showing the relative sizes of select nuclear weapons and their basic specs. Scroll down for the Mark 36.

- This now unclassified document outlines the reduction of high-yield nuclear bombs, such as the Mark 36, in favor of a larger number of smaller-yield nuclear bombs.

- In the heady years of the 1950s Cold War, at least four Mark 36 bombs were stationed in Greenland.

- Linda Sheffield Miller has written an article with recollections from her father–a B-47 Navigator/Bombardier–on carrying a Mark 36 from the UK to Spain. Apparently, taken from his unpublished book, The Very First.

- A darkly funny parts diagram illustrating the replacement of a caster on the cart that holds a Mark 36. From Alex Wellerstein’s bog, Restricted Data.