Mark 53 Bomb

Bunker Buster For Moscow’s Buried Command and Control centers

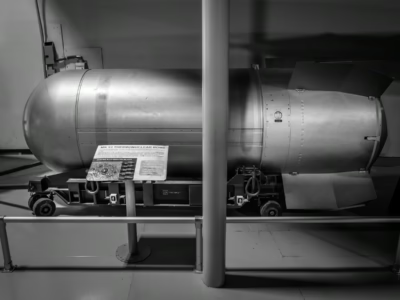

The Grissom Air Museum has a display of the B53, marking both its pride in the bomb (and especially its pride in the B-58 Hustler, which carried it) and its recognition of the nuclear accident that occured on the runway, just a few hundred yards away.

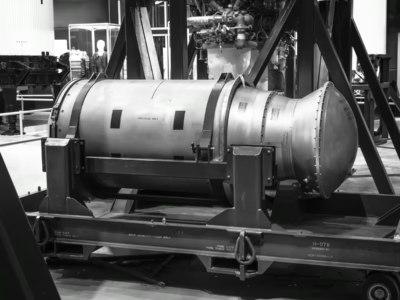

The particular B53 bomb pictured here, under the cannon-equiped tail of the B-58 Hustler, is the final B53 in the US stockpile. This unit was disassembled in 2011 and arrived the National Museum of the US Air Force in 2012.

The B53 has a complicated deployment history. Early versions were retired starting in 1967 (just five years after they were built) and out of 340 built only 25 were left in srvice by 1987 when, due to a “gap” in the Air Force’s inventory, 25 were brought back into service. By 1997 all had been retired. This unit is at the Museum of Aviation at Robins AFB, south of Georgia.

For loading into the B-52 bomb bay a weapons clip (attached to the top of the bomb) would allow crews to quickly attach the bomb to its release mechanism in the aircraft. To drop the bomb it would first be released from the mechanical lock, then small explosives would shatter the bolts that held the bomb in place. This is the only example of the harness that I have seen, here at the Nuclear Museum, in Albequerque.

The B53 was made in two versions. The most well known was the 9 megaton “dirty” version but a less substantially less powerful “clean” version was also made. Some sources say this less powerful version–which is still classified–was the more common version. This unit is located at the Museum of Aviation at Robins AFB, in Georgia.

The plane behind the B53 bomb is the B-58 Hustler fighter-bomber. One of the most interesting features of the Huster was that a special pod was designed for it that could hold fuel and a nuclear bomb, such as the B53. In use the Huslter had the ability to fly at just a few hundred feet above ground and to drop the bomb, which would then open a series of parachutes to slow the bomb’s speed, before coming to a stop on the ground. The bomb would then detonate after a timed delay. This unit is located at the National Museum of the US Air Force, in Dayton, Ohio.

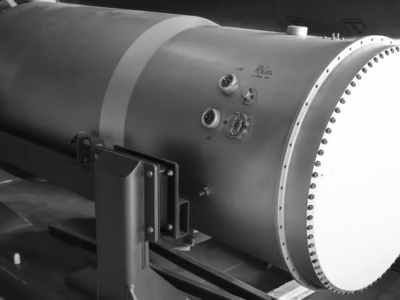

A nuclear bomb is designed inside of what is called a “physics package” (which is what you see here, at the Pima Air and Space Museum, in Arizona). The physics package would then be inserted into a bomb casing and attached to its fuzing mechanisms. Presumably, this same physics package, or one very similar, would form the warhead of the Titan II ICBM.

Although fully retired in 1997, the remaining B53s weren’t immediately disassembled, as planned. Many of the bombs, built in the early 1960s, lacked saftey features and thus required Pantex to engineer equipment and plan carefully for a safe disassembly. Not only were the nuclear elements a concern but each bomb contained 300 pounds of high explosives. The last bomb was disassembled in 2011. This unit is at the Atomic Museum in Las Vegas.

This is an image of part of the “missile gallery” at the National Museum of the US Air Force, in Dayton, Ohio. To left of the B53 bomb is the Titan II ICBM, the most powerful ICBM ever built by the United States, which used a W53 warhear–eseentially the same as the B53. Further left is a Thor ICBM and to the right is a Titan I ICBM.

This is the physics package to the B53. When used as a missile warhead (i.e., in the Titan II’s W53), the orientation of the physics package is counter-intuative: The rounded end faces the bottom of the missile, the flat part faces toward the nose. I do not know the orientation of the physics package when used as a bomb. Located at the National Museum of the US Air Force, in Dayton.

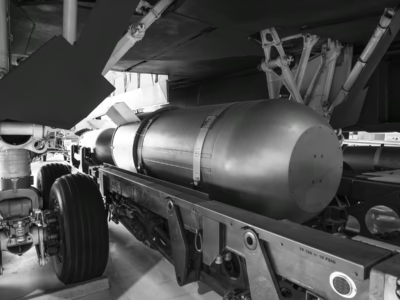

With its wide, blunt nose, the B53 doesn’t resemble anything you might think of as a “bunker buster” bomb, yet that seems to have one of its primary puposes. Prime targets included underground command centers around Moscow. The bomb’s large yield–9 megatons–perhaps make up for the lack of accurate aiming techologies in the 1960s. This bomb is at the Wings Over the Rockies Museum, In Denver, Colorado.

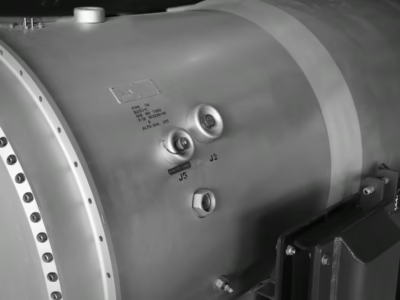

These ports are said to be the fuzing plugs for the B53. The bomb could be delivered in a variety of ways: Freefall, parachute-slowed freefall, laydown, and others. This bomb is at the Wings Over the Rockies Museum, in Denver.

The B53 is a great example of the changes in nuclear weapons brought on by advances in bomb delivery accuracy. The B53, built in early 1960s as a “bunker buster,” is 9 megatons, one of the most powerful nuclear weapons ever made. The B61 (Mod 11), which replaced it in 1996, is only 400 kilotons–less than 1/20th as pwerful, and more much effective. This unit is at the Wings Over the Rockies Museum, in Denver.

There have been two siginicant accidents involving the B53, both in 1964, shortly after the introduction of the bomb. In the first, a B-52 over the Appalachian Mountains in Maryland, lost its vertical stablizer (the vertical part of the tail that moves) and the plane crashed with two B53s aboard. Both were found “relatively intact.” In the second accident, a B-58, on the runway at Bunker Hill AFB (now renamed Grissom AFB), in Indiana, caught fire and burned. The plane also had four Mark 43 nuclear bombs on board. This photograph was made at the Wings Over the Rockies Museum, in Denver.

A “former senior officer” at SAC, as quoted in a 2010 unsigned article at the Washington Post’s web site, says that the B53 was known internally as a “crowd pleaser.” This might be due to its extraordinary 9-megaton yield but more likely was due to the dramatic scene of a B-58 Hustler dropping one at low altitude, with a trio of parachutes opening one after the other, like a flying drag racer, to slow its descent. As a photographer I like to think of it as a “crowd pleaser” because it has a certain minimalist beauty, especially so with the pod of the B-58 Hustler in the background. Located at the National Museum of the US Air Force, In Dayton, Ohio.

The B53 was test fired in Operation Dominic in 1961 and was fully retired in 1997. It was the last of the high-yield nuclear weapons in the US inventory. This bomb is located at the Wings Over the Rockies Museum, in Denver.

The B53 had a variety of fuzing options: 1)High altitude freefall, 2) contact, 3) high-altitude parachute-slowed air burst, and 4) high-altitude parachute-slowed contact burst, and 5) low-altitude laydown. In addition there was a timer for the laydown option. This unit is at the Wings Over the Rockies Museum, in Denver.

Explosive Power

9 Megaton + a less powerful version

Hiroshima Equivalent Factor

Up to 600x

Dimensions

12 ft., 4 inches x 50 inches

Weight

8850 lbs.

Year(s)

1962–1997

Purpose

A “bunker buster” bomb

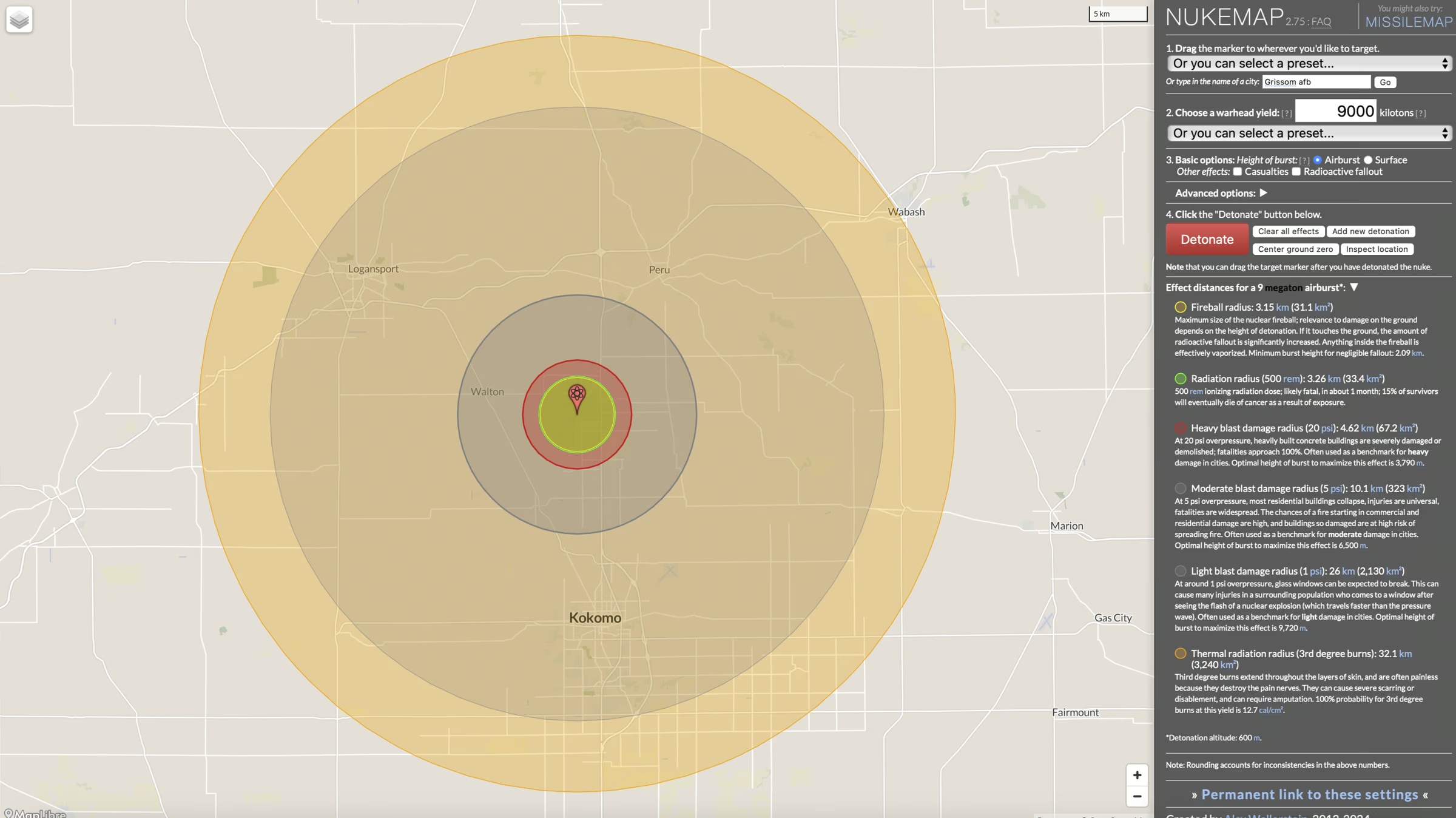

Nukemap

NUKEMAP is a web-based mapping program that attempts to give the user a sense of the destructive power of nuclear weapons. It was created by Alex Wellerstein, a historian specializing in nuclear weapons (see his book on nuclear secrecy and his blog on nuclear weapons). The screenshot below shows the NUKEMAP output for this particular weapon. Click on the map to customize settings.

Videos

Click on the Play button and then the Full screen brackets on the lower right to view each video. Click on the Exit full screen cross at lower right (the “X” on a mobile device) to return.

Further Reading

- Wikipedia, Nuclear Weapons Archive

- Sandia Lab’s “History of the Mark 53 Weapon.”

- A report made by Sandia National Labs describing the characteristics of the B53, its history and, critically, the safey hazards that led to its decommisioning.

- There have been several notable accidents involving the B53. In 1964 a B-52 bomber crashed with two B53s aboard, and that same year a B-58 Hustler caught fire on the runway while carry five nuclear bombs (one was a Mark 53) and burned out-of-control, and in an accident that brought about the removal of the Titan II (and probably the B53) from the US arsenal, a fire and explosion (non-nuclear) in a Titan II missile silo near Damascus, Arkansas in 1980. The book Command and Control (on the American Nukes list of best books) tells the story of this accident.

- The Mark 53 was used in modified form for the warhead of the Titan II ICBM (link to American Nukes forthcoming). Note: A picture from a history of the Mark 53 showing the orientation of the physics package within the Titan II warhead.